Preventing Suicide

Every one of us can help with preventing suicide and suicidal distress. The more people involved, the better.

We want the Government to continue to make reduction of suicide a priority but, in order to achieve more substantial improvements, to provide resources for mental health teams and places of sanctuary where people can be protected from their own destructive feelings and regain the will to live.

At SANE we have been warning for years of the increasing numbers of young people who harm themselves, as well as the worsening extent of the injuries that they inflict.

Suicide is preventable and we can all play a part. We know from our own research that as many as one in three suicides by people with mental illness could be prevented if crisis services were more effective and responsive.

There is an urgent need to increase the support available for these young people, who are at risk of becoming so desperate and exhausted they may take their own lives.

In 2021, there were 5,583 suicides registered in England and Wales.

The Office for National Statistics noted that the increase in the rate of deaths registered as suicide in 2021 was the result of a lower number of suicides registered in 2020, because of the disruption to coroners’ inquests caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The 2021 suicide rate was similar to the pre-coronavirus pandemic rates in 2018 and 2019. The latest available evidence shows that suicide rates did not increase because of the coronavirus pandemic, which is contrary to some speculation at the time.

Around three-quarters of suicides were males (4,129 deaths; 74.0%), consistent with long-term trends, and equivalent to 16.0 deaths per 100,000, the rate for females was 5.5 deaths per 100,000.

Among females, the age-specific suicide rate was highest in those aged 45 to 49 years (7.8 deaths per 100,000), while among males it was highest in those aged 50 to 54 years (22.7 deaths per 100,000). Females aged 24 years or under have seen the largest increase in the suicide rate since our time series began in 1981.

The one great uncertainty is how the impact of the pandemic will play out over the coming years along with rising demand for services.

Around 1.2 million people are currently waiting for mental health support, and, despite the best efforts of hard-pressed staff, data has shown that patients in crisis are twice as likely to spend 12-hours or more in Emergency Departments than other patients.

SANE is hearing from clinicians who tell us that not only are the numbers of people they are seeing returning to more normal levels, but that they are much more acutely unwell, as their condition has deteriorated due to delays, often of months, before being able to begin treatment.

“I know that I would not be here today if it wasn’t for SANE. It goes back to the constant support and care that I am receiving from your volunteers.”

SANEline caller

No time for complacency

We have been, in a certain sense, under anaesthetic over the last 18 months, and the long-term consequences for the nation’s mental health are unclear. All of which suggests that this is no time to be complacent.

We believe the majority of suicides are preventable, and in SANE’s own experience, conversation and simple interventions save lives.

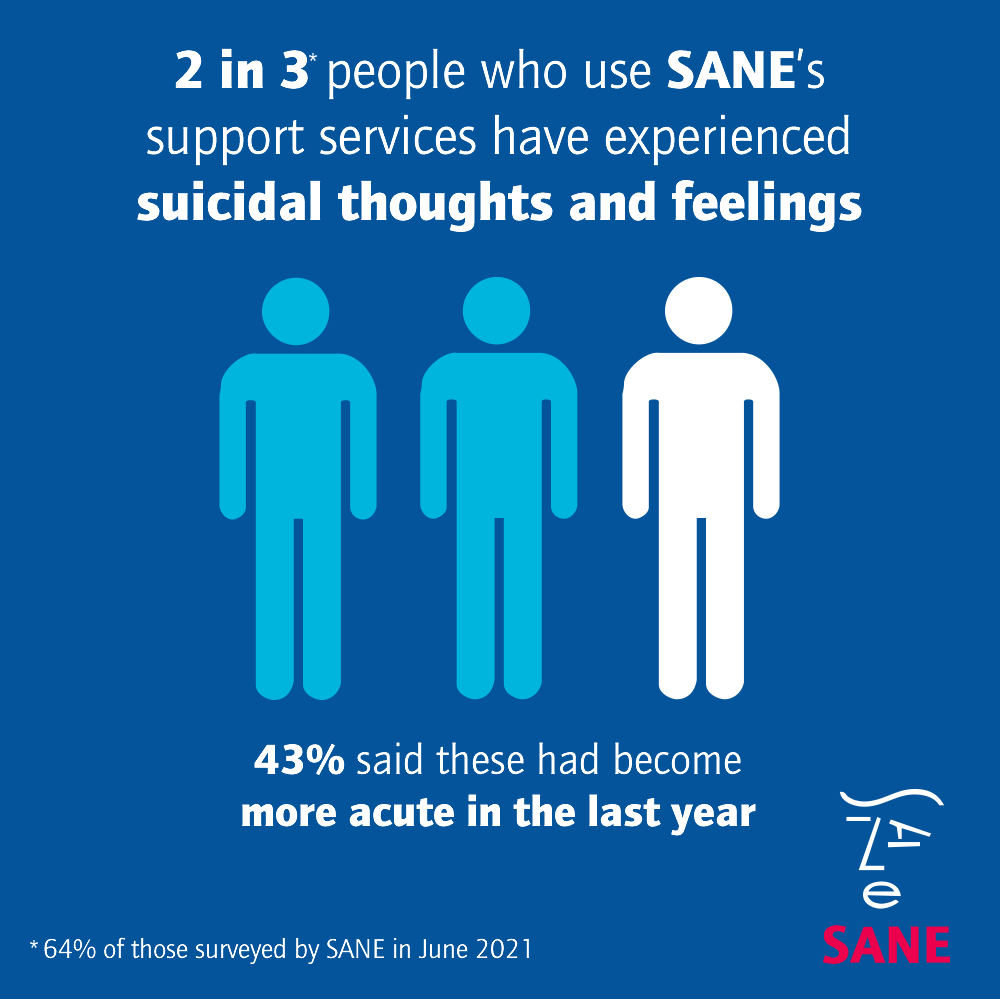

This is borne from our survey of people who use our support services, which found that over the course of the pandemic 64% said they’d experienced suicidal thoughts and feelings, and of these, 43% said these had become more acute in the last year. But 89% said that their contact with SANE had a positive impact on their mental health.

“Everyone has been lovely, and not shied away from me talking about suicide. Each person at SANE brings something different but there’s always an underlying sense of warmth, strength and encouragement.”

SANEline caller

Suicidal exhaustion

In truth, the majority of people who are suicidal do not want to die. They just find continuing as they are unbearable and are looking for a way out of the anguish they are in.

Most people we have spoken to who have attempted suicide tell us they are happy that they survived and glad to have a second chance.

Our own research into this area identified “suicidal exhaustion” as playing a key role in the decision to attempt suicide. That is to say, a person’s own lack of worth and lack of trust means difficult feelings are hidden or suppressed, possibly for months or years.

The effort required to “put on a brave face” slowly exhausts you, with no avenue to speak candidly or authentically.

This is where friends, family, neighbours – all of us – can help, by opening up an avenue for those we are concerned about, so that they may be encouraged to speak about those difficult, and potentially suicidal feelings. We should take heart in the fact that our positive intention is far more important than whether or not we get the words precisely right.

Our concern is that with mental health teams overstretched, someone who is acutely distressed to the point of suicide may not always be regarded as a medical emergency as critical as any other. We believe that if teams were given modest additional resources, and the cries for help from both patients and families taken more seriously, lives would be saved.

There is a tendency to treat suicidal behaviour as a superficial, attention-seeking problem and not as a deep internal wound. Because people are at risk to themselves, they can be regarded as less of a priority than if they are considered a risk to others.

Read our Suicide Prevention Study (PDF, 7.84MB)